Monday, January 31, 2011

Alton Brown's Buffalo Wings...

- 12 whole chicken wings (about 3 pounds)

- 3 ounces (6 tablespoons) unsalted butter

- 1 small clove garlic, minced

- 1/4 cup hot sauce

- Kosher salt

Place a 6-quart saucepan, with a steamer basket and 1 inch of water in the bottom, over high heat, cover and bring to a boil.

Remove the tips of the wings and discard or save for making stock. Use kitchen shears or a knife to separate the wings at the joint. Place the wings in the steamer basket, cover, reduce the heat to medium and steam 10 minutes. Remove the wings from the basket and carefully pat dry. Lay out the wings on a cooling rack set in a half sheet pan lined with paper towels and place in the refrigerator to dry, about 1 hour.

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees F. Remove the paper towels on the pan and replace with parchment paper. Roast on the middle rack of the oven, about 20 minutes. Turn the wings over and cook 20 to 30 more minutes, or until the meat is cooked through and the skin is golden brown.

While the chicken is roasting, melt the butter in a small bowl with the garlic. Pour this along with the hot sauce and 1/2 teaspoon salt into a bowl large enough to hold all of the chicken and stir to combine. Remove the wings from the oven, transfer to the bowl and toss with the sauce. Serve warm.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Herschel Walker wins second pro fight via TKO...

Herschel Walker continues to defy Father Time. The 48-year-old former NFL and college football star toyed with Scott Carson to pick up his second career mixed martial arts win on the Strikeforce card in San Jose, Calif.

Walker knocked Carson down with a left hook in the opening minute of their fight at the HP Pavilion and brutalized him on the ground for the next two minutes. Referee Dan Stell stepped in to save Carson at 3:13 of the first round. Walker is now 2-0 and said he plans on moving forward with his MMA career.

"MMA is my love," Walker said, when asked about talk of an NFL return.

Walker has been successful in every athletic endeavor he's attempted, so he's very demanding of himself in MMA.

"I was okay. I took a kick where I thought I was getting a little too excited," Walker said. "When you're in MMA, you should be able to take a kick like that."

Walker was a bull from the get-go.Lo Budjet "LB" Thrillkill and staff, Punka Billie Paige, Annabela Donna...

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

memphis dry rub by fb friend D.J. Watkins...

1 tbs sweet paprika

1 1/2 tsp light brown sugar

1 tsp Dark chili powder

1/2 tsp sea salt

1/2 tsp garlic powder

1/2 tsp old bay (may be hard to find away from Mid Atlantic)

1/2 tsp dry mustard

1/2 tsp fresh ground black pepper

1/4 tsp cayenne pepper

some nice spare ribs,with an easy Memphis dry rub. Cooked 3 hours, foil wrapped for 2. Cooked unwrapped for the last hour. Came out just right, no sauce just dry rub only.

southwest chili by fb friend tammy parker...

Here's my southwest chili. My 2 secrets to this chili are smoked tomatoes & peppers & Michelob Amber Bock beer. The other ingredients include chopped bell peppers, serrano peppers, onion, canned fire roasted diced tomatoes, hot sausage, hamburger, chili beans, black beans, corn, chili powder, cumin, cayenne pepper, worcestershire sauce & any other seasoning that sound good at the time. YUM-O

Ultimate Cinnamon Buns... from fb friend madilena Webb

This recipe is from Cook'sCountryTV.

Makes 8 Buns.

In step 2, if after mixing for 10 minutes the dough is still wet and sticky, add up to 1/4 cup flour (a tablespoon at at time) until the dough releases from the bowl. For smaller cinnamon buns, cut the dough into 12 pieces in step 3.

INGREDIENTS

Dough:

3/4 cup whole milk, heated to 110 de...grees

1 envelope (2 1/4 teaspoons) instant or rapid-rise yeast

3 large eggs, room temperature

4 1/4 cups all-purpose flour

1/2 cup cornstarch

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

12 tablespoons (1 1/2 sticks) unsalted butter, cut into 12 pieces and softened

Filling:

1 1/2 cups packed light brown sugar

1 1/2 tablespoons ground cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon salt

4 tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

Glaze:

4 ounces cream cheese, softened

1 tablespoon whole milk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 1/2 cups confectioners' sugar

INSTRUCTIONS

1. For the dough: Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 200 degrees. When oven reaches 200 degrees, shut off. Line 13-by-9-inch baking pan with foil, allowing excess foil to hang over pan edges. Grease foil and medium bowl.

2. Whisk milk and yeast in liquid measuring cup until yeast dissloves, then whisk in eggs. In bowl of stand mixer fitted with dough hook, mix flour, cornstarch, sugar and salt until combined. With mixer on low, add warm milk mixture in steady stream and mix until dough comes together, about 1 minute. Increase speed to medium and add butter, one piece at a time, until incorporated. Continuing to mix until dough is smooth and comes away from the sides of the bowl, about 10 minutes. Turn dough out onto clean surface and knead to form a smooth, round ball. Transfer dough to prepared bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and place in warm oven. Let rise until doubled in size, about 2 hours.

3. For the filling: combine brown sugar, cinnamon, and salt in small bowl. Turn dough out onto lightly floured surface. Roll dough into an 18-inch square, spread with butter, and sprinkle evenly with filling, making sure to leave 1/2-inch border around the edges. Starting with the edge nearest you, roll dough into tight cylinder, pinch lightly to seal seam, and, using a knife (or metal dough scraper), cut the rolled log in half and then into 8 equal pieces. Transfer pieces, cut-side up, to prepared pan. Cover with plastic wrap and let rise in warm spot until doubled in size, about 1 hour.

4. For the glaze and to bake: Heat oven to 350 degrees. Whisk cream cheese, milk, vanilla, and confectioners' sugar in medium bowl until smooth. Discard plastic wrap and bake buns until deep golden b rown and filling is melted, 35 to 40 minutes. Transfer to wire reack and top buns with 1/2 cup glaze; cool 30 minutes. Using foil overhang, lift buns from pan and top with remaining glaze. Serve.

Make Ahead: After transferring pieces to prepared pan in step 3, buns can be covered with plastic wrap and refrigerted for 24 hours. When ready to bake, let sit at room temperature for 1 hour. Remove plastic wrap and continue with step 4 as directed.

Monday, January 24, 2011

recipe from fb friend Lorri Allen...

Heres a great sauce recipe for grilled meats or mix with sour cream and use as a dip. I like to have it on hand for salsa or a finishing sauce. Try it with different bell peppers and chilies. I used red bells with fresno chilies.....yellow bell peppers with hot yellow chilies or orange bell peppers with habaneros. Great way to make colorful sauces. Sriracha Sauce 4 cups chopped chilies... I used 3 1/2 cups red bell & 1/2 cup combination of red jalapenos, serano 10 cloves of garlic, smashes 2 tsp salt 2 1/2 cups distilled white vinegar 2 TBLS light brown sugar Chop the chilies and place in a bowl. Add garlic, salt & vinegar. Cover and let set on the counter overnight or 8 hours. In the morning, remove peppers & garlic from bowl and place in saucepan. Add 1 cup of the vinegar mixture, 1/2 cup of water and the 2 TBLS of brown sugar. Bring to a boil and then simmer for 5 min. Remove from heat and cool slightly. Add peppers and 1cup of the liquid to the cuisinart and whirl until smooth. You can mix it less and make it more chunky. And you can also add more of the vinegar liquid to thin out the sauce.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Sunday, January 16, 2011

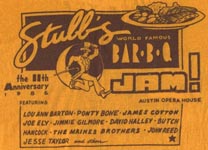

Story of C. B. Stubblefield...

as told by fb friend Wayne Hatchel.

I knew CB (Stubbs) pretty well I was the original sound engineer for the Joe Ely Band and Flatlanders. So Stubbs kept us from starving back then. Wish he was still around. I've had some good BBQ but of course Stubbs was the best. Not cause he cooked that much better (although damn good) but his sauce was the best. It is sold in grocery stores thanks to Joe Ely. We loved that old black guy and he never let any of us pay for our food. He always told us if your broke and need a meal come on out. He feed us many a Sunday night and then there would be the jam session. He was barely making it at times and Jesse Taylor asked him if he could bring a few friends out to jam on Sun. CB liked the blues and he told Jesse yes. So a bunch of us set up a little sound system and our musician friends came out. That 1st night he sold out of everything he had in the place. Man he was racking in the dough and at the end of the night. He looked at the money and looked at Jesse. He then did it again and asked Jesse you think we could do this again. And of course we did for several years Sun nite was jam night at Stubbs BBQ across the street from the area that has the South Plains Fair.

Friday, January 14, 2011

documentary on C.B. Stubblefield...

Lubbock native and longtime Austinite Joe Ely is working on a documentary on C.B. Stubblefield, the barbecue cook from Ely’s hometown of Lubbock, Texas, whose Stubb’s Barbecue is a staple of the Austin music scene. Ely started in October and has been rounding up footage and blues performers to record for the indie documentary, which he figures should ready for screenings this year.

Lubbock native and longtime Austinite Joe Ely is working on a documentary on C.B. Stubblefield, the barbecue cook from Ely’s hometown of Lubbock, Texas, whose Stubb’s Barbecue is a staple of the Austin music scene. Ely started in October and has been rounding up footage and blues performers to record for the indie documentary, which he figures should ready for screenings this year. Don May & Stubb's in 1987.

Don May & Stubb's in 1987.

Thursday, January 13, 2011

N 33° 35.057 W 101° 50.146 14S E 236811 N 3719667

Tribute to a Bar-B-Que Legend... Man's legacy brings artists, friends together for memorial

Tribute to a Bar-B-Que Legend... Man's legacy brings artists, friends together for memorialA-J Entertainment Editor

The original Stubb's Bar-B-Que at 108 E. Broadway is where everything happened. Back then? That was the 1970s and early '80s.

Those who loved music and the arts congregated in those days at Stubb's Bar-B-Que, a 75-seat, ramshackle building that provided both character and much of the finest music heard anywhere in West Texas. Today's Austin and Santa Fe-based musicians Allen, Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Butch Hancock, Jesse Taylor all honed their licks on the small stage at Stubb's.

Stubblefield gave musicians a place to play and sometimes also a place to sleep when no other could be found.

Allen was inducted into the West Texas Walk of Fame surrounding Lubbock's Buddy Holly statue in 1997; Milosevich preceded him in 1996. For that matter, no small number of Lubbock musicians who began their careers at 108 E. Broadway also have been honored with plaques on that wall: Ely in 1989, Allen in 1997, both Gilmore and Hancock in 1998.

Stubblefield, too, was honored posthumously with his own plaque at Lubbock's Buddy Holly Terrace in 1996.

But a plaque wasn't enough for the many who loved or simply remembered Stubblefield.

s Allen, whose art work is displayed internationally, is waving a fee of more than $44,000 to sculpt a bronze statue of his hero.

s Martin Outdoor Advertising, which owns the land where Stubb's Bar-B-Que once stood (the building was razed), donated a patch of property at the site for the statue.

Deborah Milosevich, executive director of the Lubbock Arts Alliance, which has overseen the Stubb Memorial Project for more than two years, indicated that the final fenced area will measure 25 feet by 75 feet.

Terry Allen's 1996 drawing depicts a statue he is sculpting of the late C.B. "Stubb" Stubblefield.

s Lubbock Arts Alliance board members showed up to personally clean the area, chopping down weeds and trimming trees.

s Lubbock musician Andy Wilkinson wrote the original copy for the Stubb Memorial Business Plan.

s Lubbock restaurateur Loyd Turner refined it and devised a spreadsheet and then made a deal with architect Ken Condray of Condray Design Group, trading Italian food for a professional site plan illustrating the actual property dimensions.

s Hugo Reed & Associates provided its surveying skills as a donation.

s The Texas Commission on the Arts supplied $1,400 in grant money for an Art in Public Places project.

s The Lubbock Area Foundation provided an additional $2,400 in grant money.

s Milosevich added, ''I talked with (Judge) Don McBeath and the county has agreed to maintain the site, which really helps. Of course we're hoping the city will want to take part; I've been visiting with Jim Bertram, Tommy Gonzalez and T.J. Patterson.''

Actually, she is hoping to raise needed funds via contributions and would prefer that the city provide in-kind services such as landscaping, fencing, irrigation and lighting.

s And an additional $1,300 has been raised via Stubb Memorial Jam concerts held in both Austin and Lubbock, at which all musicians waived their fees.

With no city funds as yet, the Lubbock Arts Alliance continues to finance the project by selling engraved bricks, each priced at $250 and destined to provide a path leading to the statue. To date, 97 bricks have been sold to businesses and individuals from Lubbock to Los Angeles, from Montana to Tennessee.

''A lot of people want their names out there,'' said Milosevich. ''Some purchased bricks as memorials for friends who have died. Some buy bricks to remember Stubb's Bar-B-Que and the part they played there.''

Ely and Tom T. Hall whose pool game at Stubb's Bar-B-Que, during which an onion was substituted for the cue ball, was paid tribute in Hall's song ''The Great East Broadway Onion Championship of 1978'' both purchased bricks. So did musicians Robert Earl Keen, Lucinda Williams and the Burk Brothers.

Other musicians who headlined concerts at that little barbecue shack: Muddy Waters, Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson...

The list goes on.

The project's business plan cites three reasons for the Stubb memorial: ''to commemorate regional music history, to commemorate the man himself, and to provide the city of Lubbock with a public work of art.''

The latter reason is not played down.

As Turner put it, ''The cost is ridiculously low and the project is generating so much positive feedback for the city already. (Sculptor) Terry Allen is pretty much an unsung benefit. This guy does big corporate art projects for major dollars and yet this is a labor of love for him.

''In a way, I think the statue will memorialize both Stubb and Terry.''

Milosevich concurs. ''It will be fabulous to have a sculpture by Terry Allen in Lubbock,'' she noted. ''I think most people around here know Terry as a musician; he was just on 'Austin City Limits' again recently. But to have a piece of public art donated by an artist the caliber of Terry Allen is extremely lucky.''

Allen whose works are on display in Los Angeles and San Francisco, as well as at the Denver International Airport and the Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis has his own reasons for volunteering his talent.

He recalled in his own ''To Whom It May Concern'' artist's statement when the project was born in 1996: ''At Stubb's funeral in Lubbock, the church was full. Half the congregation was black and half was white. The speakers were his friends and his kin. With Stubb, one was the same as the other. Color didn't mean anything that day. This says a lot. It says a lot about the man who was being buried and a lot about the community he loved ... the way he loved it and was loved back.

''From the very beginning, his cafe on East Broadway was like a big time-out from all the stupidity, phoniness and meanness of the world. It was about good food, good music and the common dignity of human beings enjoying being human in the company of one another. A lot of black and white people played music with one another on the same stage for the first time at Stubb's. A whole lot of black and white people ate food and listened to that music side-by-side for the first time at Stubb's...

''Stubb didn't play favorites except on his jukebox.''

Milosevich has her own ''personal reasons'' for devoting time to the Stubb Memorial.

''I myself was one of those who hung out at Stubb's in the '70s,'' she reflected. ''Muddy Waters, Albert King, The Fabulous Thunderbirds, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Clarence 'Gatemouth' Brown those were just a few of the musicians I saw perform there. And every week were those Sunday Nite Jams where Joe Ely and Ponty Bone and Butch and Jimmie and Jesse all played.

''It was really a magical time, and wonderful to get to be a part of that.''

That Stubblefield deserves a statue, she added, is obvious ''because all of these people have stepped forward, volunteered their time or made contributions and said, 'We're going to make this happen.' He was a generous man and people loved him.''

She also touts the project as yet another tourist attraction for Lubbock. ''Shoot, I think it will be one of the coolest things in the city,'' Milosevich noted. ''It will be both a tourist attraction and a music attraction. People will flock to this statue the same way that musicians drive out to the cemetery put their (guitar) picks on Buddy Holly's headstone.

''It certainly will be more shrine than roadside attraction.''

Asked what she thought Stubblefield himself might think about the effort, Milosevich answered, ''He'd probably just laugh really hard if he was here.''

Still, the project is not complete. Even as Allen begins working with clay on the statue's armature, money must be raised. Businesses and individuals wishing to make contributions of money or service stonemasons and bricklayers will be needed, said Milosevich or purchase engraved bricks should call the Lubbock Arts Alliance at 744-2787.

Milosevich would like to see the project finished and the statue erected by September, and sees light at the end of the tunnel though $30,000 still needs to be raised.

Turner said, ''That would be perfect and I don't see why it can't be done. Having it finished in time for the Buddy Holly (Music) Festival would be great timing.''

He continued, ''I see this statue as a very healing thing for the city, especially in light of the recent Hampton (University) incident. Plus, we don't have that many 'characters' to honor. How many people do you know who owned a barbecue joint, was loved by musicians, was featured on David Letterman's show nationwide and is still talked about, still part of the Lubbock consciousness?

''Something happened at Stubb's Bar-B-Que that needs to be memorialized.''

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Stubb Stubblefield: Archangel Of Barbecue...

"But one of my favorite stories about Stubbs happened one day when I was sitting at the bar. Everyone in the place was black except me. In walks this Hispanic man. He looks at the crowd and then asks Stubbs: ‘You serve Mexicans here?’

"But one of my favorite stories about Stubbs happened one day when I was sitting at the bar. Everyone in the place was black except me. In walks this Hispanic man. He looks at the crowd and then asks Stubbs: ‘You serve Mexicans here?’ Stubbs eyed the man ominously, then answered: ‘No. We serve barbecue here.’"

by The Kitchen Sisters

March 20, 2009

From 1968 to 1975 in Lubbock, Texas, C.B. "Stubb" Stubblefield ran a barbecue joint and roadhouse that was the late-night gathering place for a group of local musicians who were below-the-radar and rising: Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Willie Nelson, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Muddy Waters, Johnny Cash, Tom T. Hall.

"I'll never forget when Linda Ronstadt came," Ely's wife, Sharon, recalls. "She went into Stubb's kitchen in her little white ballerina slippers and walked through the most barbecue sauce-encrusted floor I've ever seen."

Stubblefield, born poor and hungry, had a kitchen calling. He wanted to feed the world — especially the people who sang in it. He had been an Army cook in the last all-black regiment of the Korean War. Back home in Lubbock, he generously fed and supported both black and white musicians, creating community and breaking barriers.

Lubbock was very segregated back then, recalls singer/guitarist Gilmore. "One day [blues guitarist] Jesse [Taylor] was hitchhiking, and this big huge black man stopped and picked him up. It was Stubb. C.B. Stubblefield. He had a barbecue joint, a tiny little dive, and Jesse started hanging out with Stubb. ... At some point, Jesse said, 'Stubb, could I bring a few of my friends and play?' It was unusual for a white kid and a black man to become close friends."

"The place was about barbecue and music," says country music singer and songwriter Hall. "You knew if you wanted to hang out with your kind of people, you could go out to Stubb's and see a bunch of pickers out there. It was like camels to a watering hole. And he loved musicians. He was kind of an archangel."

But Stubblefield had "zero business sense," Gilmore says.

And no money, Ely adds. "Everybody tried to help him, and eventually we got him to make some barbecue sauce in the kitchen, and then we'd take it out and sell it for him."

"We had an organization we called the IRS: Idiots Rescuing Stubb," Hall says. "Once in a while Stubb would go out of business, and we'd all get together and raise some money and put him back in business."

According to Hall, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings were members of the club.

In 1985, Stubblefield moved to Austin and opened Stubb's, a legendary club with a legendary sauce, that still opens its doors to new talent pouring into town each year for the South by Southwest music conference.

When we produced the Hidden Kitchens Texas radio special, we recorded music for the hourlong program in Austin at KUT studios with Gilmore, steel guitar player Cindy Cashdollar and bass player Tom Corwin. During the recording session, Ely came by. Gilmore and the Elys are longtime friends from Lubbock. When we started talking about Hidden Kitchens Texas, the conversation quickly turned to Stubb.

"Stubb had this deep, beautiful voice," Gilmore says. "He just exuded love. He'd get up and say, 'Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Stubb, and I'm a cook.'"

"I never had any Stubb's barbecue," Hall says. "Stubb and I were great friends. I loved him like a brother. But I never told him — I was a vegetarian."

Produced by The Kitchen Sisters, Davia Nelson and Nikki Silva, with Laura Folger and Nathan Dalton. Mixed by Jim McKee.

Smoking a whole beef brisket requires deep commitment — literally. Plan on 1 1/2 hours per pound of brisket. This means at least 15 hours for a "small" 10-pound brisket, and 24 hours for a 16-pounder! But once the meat's on the grill, the hard labor's done. Just tend to the temperature, the smoke and, if desired, give it an occasional mop. Stubb's Restaurant Rub For Meats

Makes about 1 1/2 cups; enough for a large brisket or three slabs of ribs

1/2 cup black pepper, preferably medium ground

1/2 cup Stubb's Bar-B-Q Spice Rub

1/4 cup granulated garlic or garlic powder

3 tablespoons onion powder

2 tablespoons all-purpose seasoning salt

1 9-to-11-pound trimmed brisket, with about a 1/4-inch layer of fat

2 cups Stubb's Moppin' Sauce (optional)

8 cups woodchips, or 12 chunks, soaked

Barbecue sauce (optional)

In a small bowl, combine the pepper, Spice Rub, granulated garlic, onion powder, and seasoning salt and set aside

Rinse the brisket and pat dry with paper towels. Generously coat the brisket with the spice rub mixture on all sides. Brush with mopping sauce (if using). Let it come to room temperature while the grill fires up.

Prepare a grill for indirect cooking. For a charcoal grill, when the coals are ashed over, rake or spread them out in one part of the grill so the food can cook to the side and not directly over the coals. (For a gas grill, fire up the burners on one part of the grill, so the food can cook to the side of the heat but not directly over it.) Cover the grill and bring it to around 225 degrees. Drain and add one-quarter of the wood for smoking.

Set the brisket over indirect heat and cook about 1½ hours per pound. To ensure even cooking, set an oven thermometer next to the brisket, also over indirect heat. Every hour, check it and add more fuel and wood as needed to maintain a smoky 225-degree heat. Cook, mopping every 2 to 3 hours (stop mopping one to two hours before you think the brisket will be done), until the internal temperature reaches 185 degrees. Let the brisket rest 15 to 45 minutes. Slice the meat against the grain and serve plain or with barbecue sauce on the side.

1 pound dried black-eyed peas or other beans

1/2 pound thick-sliced smoked bacon, cut into ¼-inch wide pieces

1 medium onion, cut into small dice

2 ribs celery, cut into small dice

1/2 red bell pepper, cut into small dice

1/2 green bell pepper, cut into small dice

4 cloves garlic, minced

2 to 3 teaspoons salt, or to taste

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Olive oil and wine vinegar (optional)

Pick through the beans to discard any pebbles or other debris. Rinse the beans well. Soak in plenty of water to cover for at least four hours or overnight. Drain the beans and set aside.

In a heavy pot, fry the bacon over medium-high heat until it browns, about 10 minutes. Stir in the onion, celery, bell peppers, and garlic and cook, stirring occasionally, until the vegetables soften but still have some crispness, about 5 minutes. Scoop out half the mixture and set aside (refrigerate if you're not planning to serve the beans as soon as they're cooked.)

Add the beans to the remaining vegetables in the pot and enough water to cover by 1 inch (6 to 8 cups). Bring to a boil over high heat, then reduce the heat so the beans slowly simmer. Do not cover the pot. Start testing after 20 minutes, though they may take as long as one hour. When the beans start to feel soft, stir in the salt and pepper. Stir the beans occasionally as they cook; they're done when just tender, but not much. (Note: For a thick bean broth, puree 1/2 to 1 cup of the beans and return them to the pot.)

Ladle the beans, with some of their liquid, into bowls or cups. Spoon on some of the reserved bacon mixture (reheat if necessary in skillet or microwave). For extra flavor, drizzle with olive oil and a splash of vinegar to taste.

"A Captain without a Ship"

"You know that sign…the one from the old building that said, ‘THERE WILL BE NO BAD TALK OR LOUD TALK IN THIS PLACE’? Well, I’d been hanging around Stubb’s for about 5 years when I suddenly noticed that there were three words in the sign stenciled in red and the rest were stenciled in black. The three red words were ‘bad,’ ‘loud’ and ‘place.’ From that day on, I couldn’t see that sign it didn’t say to me, ‘BAD LOUD PLACE.’ That’s what that sign said."

"You know that sign…the one from the old building that said, ‘THERE WILL BE NO BAD TALK OR LOUD TALK IN THIS PLACE’? Well, I’d been hanging around Stubb’s for about 5 years when I suddenly noticed that there were three words in the sign stenciled in red and the rest were stenciled in black. The three red words were ‘bad,’ ‘loud’ and ‘place.’ From that day on, I couldn’t see that sign it didn’t say to me, ‘BAD LOUD PLACE.’ That’s what that sign said."C.B. Stubblefield:

"A Captain without a Ship"

By Michael Hall

(This article originally appeared in

The Austin Chronicle, January 25, 1985*)

People get nutty about barbecue. More so than with burgers, more so than with Tex-Mex, more so, I suppose, than with French cuisine. They plan their days around barbecue. They dream about it. They travel to Kansas City and Chicago to eat it. Barbecue is All-American – beef, chicken, pork, meat. Yet it differs region by region, cook by cook.

People used to travel to Lubbock for barbecue. Through a land of desert sameness to a place alive with contrast, music, and some of the best barbecue in the country. Stubb’s Barbecue – where a black man in the wilds of white West Texas dished up home-grown philosophy with the meat, and hosted late night dream jam sessions with the famous and the then-unknown, who played as long as the sauce and beer flowed. A huge man, a legend, with the nickname "Stubb."

Well, Lubbock has never been a very coherent place. The musicians, artists and weirdos born on the wind and sage there are well-known. Stubb, born C.B. Stubblefield, was just one more artist, pulling genius from desolation. He has become something of a folk hero – his travels, his ties with musicians, his troubles, and most of all his barbecue, make him loom larger than any man’s natural life. Now he’s in Austin, where his reputation has preceded him, but where he is, in his words, "a captain without a ship."

Stubb’s story begins with his craft. As with all master cooks, cooking is no mere diversion to Stubb. It’s his life, his art. "I love to cook," he says. "I love to feed people. That’s my pride, above all else. I love music. I love people, but I’m gonna do my fair share by putting out what I consider the best possible barbecue you can put in your mouth."

Responsibility, doing one’s fair share, is a recurring theme in Stubb’s philosophy. It grew out of a large family, all cooks, and the times and places he grew up and lived in. "My family is ‘Cooking Unlimited,’ I call it. Nothing to brag about – it’s just the way we feel about food. My brothers are all the same way – they love to cook. We just grew up in it."

Stubb was born in Navasota, Texas; his family moved to West Texas when he was young. "We were sharecropper’s sons in the old hardcore American way of life," he recalls. "My dad was a Baptist preacher. He loved God, he loved people, he loved America. After that he loved horses. He could ride a horse like nobody’s business. A lot of people tried to get him killed on a horse. They’d bring the most dangerous horse in the world around – the white folks would – say ‘we’ll see this horse kill this nigger.’ My daddy fooled em, you know. He fooled them more than one way. He didn’t rebel against society – he accepted – but he knew who he was. And he was strong. My dad was a strong man. He was a good cook."

Cooking, as a birthright, bred self-sufficiency, and then identity, strengthened, or hardened, in the face of hard times and racism. Through it all though, Stubb, like his father, became more determined than bitter, a rugged individual in the mold of those who preceded him on the plains of West Texas. His pride is bottomless; his faith in the promise of an American way is firm.

"I don’t think, with the price I’ve had to pay in this society…" he begins, then trails off. "See, I’ve been to war – I got battle scars. I know what the true values of Americanism is all about. I know now when I was a child you couldn’t go to the same facilities as a white person could, simply because you were black. Not because you was a person. Black means your identity, you know. Now, I don’t think I could stand that. When you go out and you see your friends die on the battlefield, for democracy…I don’t believe in forced integration, I don’t believe in forced nothing. I believe in the right, the will, as American people. I don’t believe in black power or Black Moslems or voodooism or Ku Klux Klan – I believe in the will as an individual. You do your thing, I do mine. But let’s meet in the..., kinda like the Olympics – participate as a people. If you win the gold, you win the gold. I’m not gonna make a run and try to take it away from you."

Indeed. Not just locals who stumbled onto Stubb’s barbecue. Joe Ely and Jesse Taylor began hanging out at Stubb’s, and passing the word on to other musicians. The inevitable happened, and Stubb’s became a haven for local and touring musicians. The list of folks who ate and played at Stubb’s is long and wide. "Name it – you want a rock ‘n roller, a boogie woogie, or blues, or whatever – it’s been there." Linda Ronstadt and Emmylou Harris; a couple of Rolling Stones, a Beatle or two. Tom T. Hall wrote a song about Stubb’s and the legendary pool

Stubb’s barbecue became so popular with certain musicians, some pleaded with him to move, to anywhere but Lubbock. A few offered Denver. Ely, after he moved to Austin, hinted at a location closer to his new home. Hall, Bobby Bare and Johnny Rodriguez tried their best to get Stubb to move to Nashville. But Lubbock was Stubb’s hometown. He was too much a part of the city’s peculiar, grand-in-its-own-way scenery. And there was something almost spiritual about all these people traveling so far for their meat, their barbecue salvation.

Maybe it was a combo of good barbecue, cold beer, and the late night blues and country music that made Stubb’s special. Maybe it was the paternal joy with which Stubb presided over it all. But Stubb now knows the value of Stubb’s BBQ in Lubbock. "I’ve had some people call me since I’ve been in Austin – wanting to know when I’m gonna open that place in Lubbock. I’m talking about Johnny Cash, Tom T. Hall, all these people, Joe Ely and the whole ball of wax; they knew the real value. I didn’t know we were havin’ such a value ‘til they came out of that place."

Mastering one’s art usually leads to unfamiliarity with some others, and Stubb’s devotion to barbecue left him vulnerable to the hard realities of running a business. "At Stubb’s BBQ we got to be multimillionaires in love and affection, but we didn’t make any profits – monetary stuff." He laughs when he says this, but the bitterness of having to leave his hometown still lingers. He owed taxes, and the IRS threatened to close him down if he didn’t pay. So he closed it down himself.

Stubb left Lubbock in March last year, tried his luck in Santa Fe, and came to Austin in June; he began working at Antone’s in October. Blues and barbecue are a natural, but for Stubb it isn’t the same as it was in Lubbock. He is a welcome addition at Antone’s, and he likes cooking there, seeing some similarities between Stubb’s in Lubbock and Antone’s in Austin. But it’s not Stubb’s in Austin.

"I’m working as a captain without a ship," he laments. It will have to be that way – cooking, but not running his own place – until he gets things straightened out with the IRS.

Displaced, almost hidden, (you can’t miss Stubb’s when you walk in, but you can driving by), Stubb has not found the due he expected he would in Austin. The lunch and dinner crowds are mere trickles, though he does some late-nite business, staying open long into the bands’ sets. He is disappointed that his fame has not yet kept step with his move. "I’m just not satisfied with what I’ve done in Austin so far," he says. "I’m just a bit confused. And Lubbock has been on my mind. It’s a transition – I’ve got to get it motivated into my system and do the same things I did in Lubbock. And let the good things come out that I know are in me."

He likes Austin, and gets many customers who frequented Stubb’s in Lubbock, like the three UT students from Lubbock who one dinner hour regaled me with myths about the old times before they devoured their beef plates.

"I had a strong relationship with Austin before I got here – I enjoyed it. Austin is a good town. You got an attitude in Austin and I think that’s great. People don’t mind telling you – ‘say man, that’s good barbecue.’ And that’s the basic thing right there."

Word is spreading about Stubb and his barbecue – he already has new groups of regulars. He is also putting on some good publicity moves, like his Saturday’s "Major Rib Eating Contest" at Antone’s. It’s all you can eat for $25 (you can eat a lot of ribs for $25). And he/she who eats the most ribs wins a barbecue party for 10 plus $100; second prize is a barbecued turkey; third is a barbecued ham. Deadline for entry is Friday noon; the contest starts Saturday the 26th at 7 p.m.; and the number of entrants is limited, so sign up soon. And start fasting.

What is Stubb’s secret; how is his different from all the other barbecue in and around Austin? "I wonder about that sometimes. I wonder if it's the love and care that I do to it. I’ve eaten a lot of barbecue in Austin, Texas and I can say, not to take anything away from the other barbecue places, it just don’t taste like I want it to taste."

About his recipe, Stubb says "I guess it was born into me. I come from a family of cooks. There ain’t a cookbook in this building that I look at. You don’t get it from a cookbook. You get it from … the feeling."

That "feeling" has made Stubb a bona fide legend in his own time. "Me? I feel like a legend, whether I like it or not. I don’t hardly accept it. But when I go around to towns and meet people and they say ‘there goes Stubb.’ …some never saw me before. I was in the airport in Albuquerque, New Mexico, this lady came up to me and said ‘Ain’t you Stubb?’ In Chicago, same thing – 'I heard about you.’ This I credit to people I know. People talk about Stubb’s all over the world.

"Me and (artist) Paul Milosevich, we were up visiting Tom T. Hall and he came up and looked at me and Paul and said ‘you know what? You two guys are the brokest damn legends I ever saw in my life!’ "

Broke or not, Stubb vows to keep on. He knows the value that can’t be figured in ledgers, the strength that comes from pride, and he knows nothing but faith. "I just figure that the old man upstairs will open up some doors and avenues, that can do this thing the right way. It’ll work itself out, I’m sure. Everybody who comes in really loves the food – that’s the only thing I’ve got and that’s what I want most."

If it’s a tribute to this country that a sharecropper’s son can become a world-renowned cook, and wind up doing what he loves to do, it’s a damn, mean shame that when his chips are down, the powers that be can’t find it in their hearts and pockets to stack them back up again. There is an ugly truth latent in the promise of the American Dream – you make it on your own, but when you fall, you fall alone. It’s a dream Stubb followed and found, and it has now, in its natural course, turned on him.

Like other self-made men, Stubb is embarrassed by assistance. Benefits, like the

But I like to think that Ely and his pals were just doing their fair share, to keep Stubb among us. Stubb has done and will continue to do his part; his life is a reminder to the rest of us to do the same.

"Stubb's Bar-B-Q... Texas Baby!!!

C.B. with the Joe Ely Band.

C.B. with the Joe Ely Band. Buddy Guy, C.B. Stubblefield, & Stevie Ray Von. I am so proud to be from Texas. sr

Buddy Guy, C.B. Stubblefield, & Stevie Ray Von. I am so proud to be from Texas. sr

the original Stubb's Bar-B-Q on East Broadway in Lubbock.

- "I was born hungry; I wants to feed the world."

- "Bar-B-Q? Makin’ do with what you got."

- "God born me a black man and I plan to stay that-a-way."

- "They build barb wire fences around old locomotives. I’ll be damn if they do that to me."

- When asked how he was while in the hospital:

"My Spark plugs ain’t firing, and I got this tornado loose in my chest." - "I guarantee you one thing, you ain’t gonna cook no better than I can. Another thing, you not gonna love people no better than I can."

A silent graveside memorial will be held for the late C.B. "Stubb" Stubblefield at 2 p.m. today at his grave site at Peaceful Gardens Memorial Park, located on the Woodrow exit off South US Highway 87.

Although the new cemetery marker for Stubblefield's grave was installed on May 12, the memorial was planned for today, the fourth anniversary of Stubblefield's death.

The original grave marker, provided by the U.S. Army, was taken by an unknown person before its final installation in 1995 and never returned.

The new tombstone was financed with funds raised from private donors and at benefit concerts.

On Sept. 15, 1998, Stubblefield supporters P.J. Welch-Liggan and Karen Vogel chose a design for the brass marker that includes a reproduction of Lubbock artist Paul Milosevich's drawing of "Stubb" and the words from the late barbecue entrepreneur's restaurant: "There will be no bad talk or loud talk in this place."

Bobby D. Assiter, president of Peaceful Gardens Memorial Park, said that "Stubb" paid for three cemetery plots in the 1960s with his legendary barbecue.

Stubblefield was inducted into Lubbock's Buddy Holly Terrace in 1996.